By Georges Pierre Sassine, Olga Antoine Jbeili

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Daily Star on January 22, 2013, on page 7.

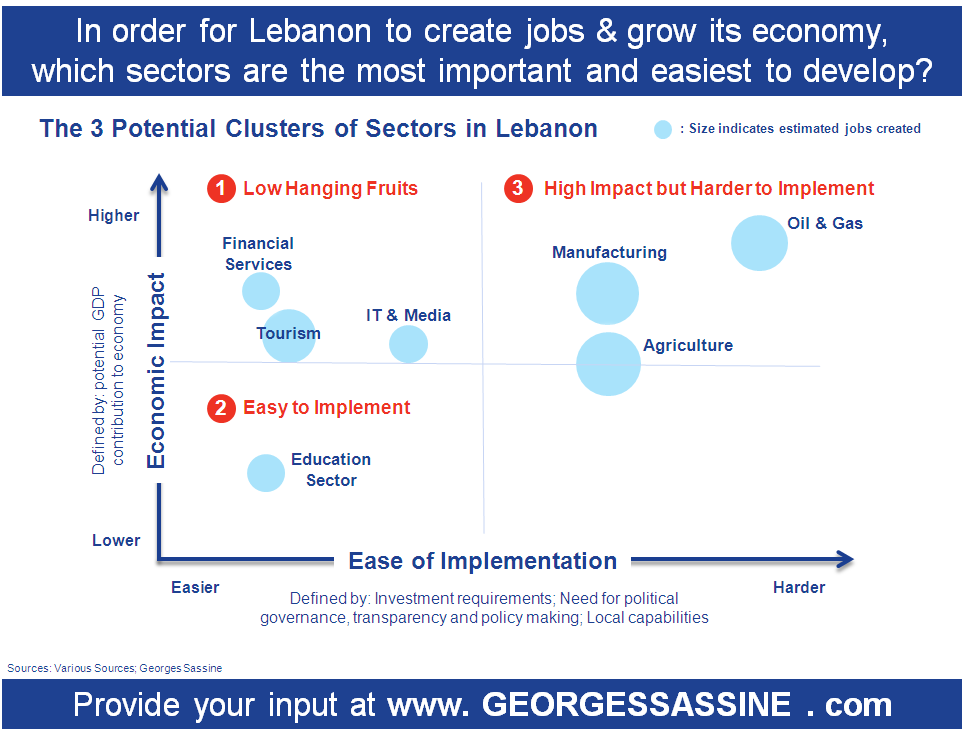

Political instability has become the norm in Lebanon. The country’s economic and political outlook seems to be tightly dependent on regional developments, especially in Syria. In 2012, Lebanon’s economic growth stood at 2 percent, falling significantly from an average 8 percent between 2007 and 2010. Analysts expect future growth of Lebanon’s tourism and financial services sectors to be negligible until a resolution is reached in Syria.

However, there is tangible hope in sight and Lebanon’s economic outlook can be improved regardless of the current uncertainty plaguing the country.

Risk and complexity are here to stay. Therefore, Lebanese businesses and government must learn to adapt. One approach is to identify global trends and find ways for Lebanese to leverage them.

For example, the U.S. National Intelligence Council, representing the 17 intelligence agencies of the United States government, recently published a report fleshing out global trends during the next 15-20 years. The NIC report highlights different scenarios of how the world could unfold, but also identifies megatrends that will likely occur under any scenario. Lebanese decision-makers should think and plan for the long term and find opportunities in these trends that are most likely to occur.

Lebanon’s economic outlook can be improved regardless of the current uncertainty … One approach is to identify global trends and find ways for Lebanese to leverage them.Georges Pierre Sassine, Olga Antoine Jbeili

One of the megatrends identified by the NIC is an increase of the global population by more than 1 billion people by 2030. This will put strains on food and water resources where demand for food will increase by 35 percent, and the global food production outlook will worsen due to climate change patterns.

Higher and volatile international food prices are already negatively affecting Lebanon – which imports more than 80 percent of the food it consumes – and will continue on driving up local food prices in the future. This will provide a unique opportunity for Lebanese farmers and entrepreneurs to expand domestic agriculture production and improve Lebanon’s food security. Specific measures include incentivizing investments in Lebanon’s agricultural sector, a strategic shift to high-yielding grains, crop diversification and developing irrigation infrastructure.

In addition, the growing demand for agricultural resources has also been driving countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait and China to acquire farming lands in foreign countries, mainly in Africa, in order to ensure their food supplies. However, land acquisitions have been leading to disastrous consequences for poor communities – as families are kicked out of the acquired lands – and attracting sharp international and local criticism.

The well-established Lebanese diaspora can then play the role of middleman and help make these land acquisitions more sustainable. They can facilitate cooperation and communication among foreign investors, international organizations, African governments and local communities ensuring more equal benefits to all parties involved. Lebanese can also play several roles across the agriculture value chain: Opportunities are not limited to the farming of acquired lands but also include food processing, agro-industrial and agribusiness services, traders and other businesses at multiple levels from the farm to consumers.

The Lebanese government can play a big role in enabling such opportunities to national businesses. Laying the groundwork for partnership with countries such as China and Gulf countries in Africa and stressing the involvement of African partners will be critical. Such cooperation will be an evolving process with few precedents but an opportunity that should not be missed.

The NIC report also suggests rapid urbanization in the developing world to be another megatrend certain to be witnessed. The volume of urban construction for housing, office space and transport services over the next 40 years could roughly equal the entire volume of such construction to date in world history.

This could have serious consequences for Lebanese construction companies, engineers and architects. While the construction industry, one of the most vibrant sectors of Lebanon’s economy, has traditionally focused on domestic and regional markets significant new opportunities could be reaped elsewhere.

According to the United Nations, 11 countries will contribute to 62 percent of the world’s urban growth by 2030 including China, India, Brazil, Mexico, Nigeria and the United States. Lebanese can and should play a role in helping serve the construction needs of urban formation and expansions in such countries. Demand in the Levant and Gulf countries will continue to come primarily from foreign markets for Lebanese developers, but diversifying to new growth destinations could set them up to unprecedented growth. The competitiveness of Lebanese businesses in these future markets can be improved if they start tapping today into Lebanese emigrant networks, chambers of commerce, Lebanese embassies and Lebanese banks which could facilitate access to credit for their expansion plans.

Fundamental changes to the mindset, capabilities and organization of Lebanese institutions are required.Georges Pierre Sassine, Olga Antoine Jbeili

These are a few illustrations of the myriad opportunities that Lebanese businessmen and policymakers can identify if they incorporate long-term planning in their decision process. Political instability is likely to persist and the only way to secure Lebanon’s future is to adopt a flexible, innovative and adaptive approach to policymaking. It requires fundamental changes to the mindset, capabilities and organization of institutions. Tools like scenario planning, policy gaming and horizon scanning should all be added to the decision toolbox in order to secure sustainable development for future generations.

In summary, growth and opportunity are possible for Lebanon if private and public institutions are redesigned for new times.

Georges Pierre Sassine is a public policy expert and a Harvard University alumnus. Olga Antoine Jbeili is a development economist and a University of Sussex alumnus. They wrote this commentary for THE DAILY STAR.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Daily Star on January 22, 2013, on page 7.

(The Daily Star: Lebanon News: http://www.dailystar.com.lb)